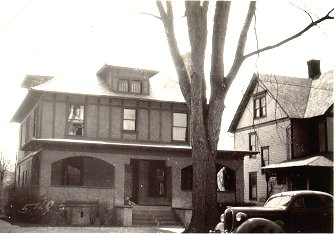

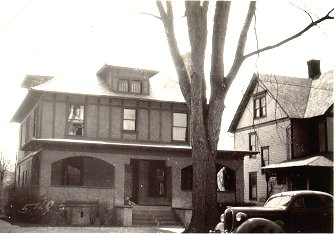

139 Leroy Stree as it looked in 1939

139 Leroy Stree as it looked in 1939 139 Leroy Stree as it looked in 1939

139 Leroy Stree as it looked in 1939

A house at 139 Leroy Street was always home to Mother and Dad from the time they were married, though it was not always the same house. I believe that Dad's father had given him four lots from the Bennett tract --139 and 141 on the south side of Leroy Street and 66 and 68 directly behind on the north side of Lathrop Avenue.

| When they first moved in, their house was almost the only one in the area. Surrounded by open fields, it was practically the last one out Leroy Street, which, at that time, extended only to Rotary Avenue. Their view was unobstructed to Riverside Drive, as very few houses existed on any of the intervening streets. |

|

Their first home was a grey clapboard frame house. This was moved about l908 from l39 to l4l and the present stucco house was built at l39. I don't know for sure the reason for the move, but I believe Dad was in some sort of mail order business as well as the Marean-Lauder men's clothing store; and though he wanted a different house, he also wanted the same address.

The new house, designed by an architect named Lacey, was unique in a number of ways. Its basic plan had to conform to the plan of the old house, so that the original foundation could serve as the foundation for the new structure. This was altered in only a few instances, and the old stone cellar wall is still visible in places where the plaster facing has worn off.

In the early 1900's electricity was a new and not always satisfactory way to light a house. Gas was more dependable. Many of the original fixtures in this house were combinations, both gas and electric. When the electricity failed, the gas could be used. Such fixtures were in two wall lamps over the living room mantle, beside the bed in the master bedroom, (where Mother lit the gas flame to heat the curling iron she used for her hair), in the downstairs lavatory and the upstairs bathroom. Though the gas elements were not used often, they were most helpful at times, and remained functional until after Dad's death, when we bought the house from Mother. Then, because we were afraid of possible gas leaks, we had the gas shut off at the source in the cellar; and most of the old fixtures were replaced with ones that were electric only. In the upstairs bathroom, where the fixture was for gas only but not electricity, I believe the cap on the gas pipe can still be seen on the west wall, to the right of the medicine cabinet.

There was one innovation for the times that was never really completed. This was a central vacuum system whereby the busy housewife could clean the whole house without having to empty a vacuum cleaner. Pipes that were built into the walls of the house led to a unit in the cellar where all the dirt was to go. The vacuum cleaner was to fasten by hose to the baseboard pipe outlets (located in the upstairs and downstairs halls). Since the pipe outlets were fairly central on both floors, a person was supposed to be able to reach all the rooms from the two outlets. For some reason, the vacuum cleaner itself never materialized, and the pipes never carried our house dirt to the cellar.

Houses at the time were heated with coal, which was delivered in horse drawn, or later motorized, vehicles whenever ordered from the coal company, perhaps two or three times a winter, depending on the severity of the weather and the capacity of the coal bins where the coal was stored in the cellar. Coal bins were an important part of every cellar plan. Where necessary, men who delivered coal carried it on their backs in large open canvas bags from the truck to the coal bins. At our house men did not have to do this but could drive their wagon up to the side of the house, extend a metal chute from the truck through a cellar window and send the coal clattering noisily directly into any of the three coal bins along the west cellar wall. Two of these bins were for the furnace that heated the house, and one was for the little stove that heated the hot water. Different sizes of coal were used for the different purposes. We used a hard, blue tinted coal (called pea coal, I believe), but some people used larger chunks. This was cheaper, but also softer, smokier, and probably less efficient.

It was important to tend the fires each day, or they would go out, and there would be no hot water or no heat in the radiators throughout the house. Dad shook the ashes from the top part of the hot water heater every day into the small ash pit at the bottom of the stove. These he removed by shovel into a large ash can which, when full, he took up the back cellar stairs to the outside. Most men had to do the same thing with the furnace, but not Dad! Our furnace had a special feature. Like other furnace tenders, Dad had to shovel coal into the furnace, but he didn't have to do it every day. The furnace had a separate part where Dad stored coal until it was needed. Then the furnace automatically transferred it to the fire box.

Nor did Dad have to shovel ashes out of the furnace. The furnace sat atop one half of a circular pit which was about three feet deep in the cellar floor. The pit was approximately six feet in diameter and contained an iron framework that held six triangular shaped open metal cans. The cans were rotated, like colorful wooden horses on a small merry-go-round, by means of an iron bar fitting into a hole just in front of the furnace and reaching the center of the metal framework. When the ashes were shaken out of the fire box, they went down into a can in the pit, under the furnace. When this can was full, the framework was rotated until the next can was under the furnace. This rotation continued until all cans were filled with ashes. Then Dad removed the triangular metal cover over a triangular opening in front of the furnace and by means of a pulley, hauled each can out of the pit. As soon as all cans were sitting on the cellar floor, they , too, were hauled up the back cellar stairs to the outside. This seems like a lot of work to those of us who regulate our house heat by the turn of a thermostat, but it was easier than shoveling ashes and then carrying them up a flight of stairs to the outside every day.

When the house was built, the word "refrigeration" meant ice box. Our ice box was built to be as much a labor-saving device as possible. The ice compartment in the upper left half of the box had two doors, one in front and one in back. Both opened out. The one in back was opposite a similar sized door through the back house wall, opening onto the back porch. This arrangement made it possible for the ice man to deliver ice to us without ever coming into the house. He put the ice into the ice box through the two back doors. We took it out through the front one.

Our ice box had another handy feature. The scientific basis for the ice box, of course, was that as the ice melted, it kept the food in the ice box cool. This made a problem, too. The melted ice water had to go someplace. In most homes this meant into a basin under the ice box, and woe to her who forgot to empty the basin in time! Water spilled all over the surrounding floor. We had a better system. Our melted ice flowed through a pipe in the ice box, then through a funnel and into a pipe that reached through the floor and emptied outside under the back porch. This worked great, except on cold winter mornings when the pipe outside got frozen and the water backed up. Then, after one accicent, we had to adopt the basin emptying routine until the pipe thawed again.

Most people had ice delivered two or three times a week from Cutler's Ice Company. Their ice was cut each winter from Cutler's Pond on the west side of Upper Front Street, not far from where Sunrise Terrace is now. Once sawed from the pond,the chunks of ice were buried in sawdust in the big ice house nearby., to protect them year round from the heat. Ice was sold in chunks of 25, 50, 75, and 100 pounds. Purchasers indicated their needs by placing a square cardboard sign in a front window. This sign had a different number on each side (25, 50, 75, 100), and the number that was placed at the bottom of the sign told the ice man how much ice to deliver.

Ice was never charged, was always paid for upon delivery, but no cash exchanged hands between the purchaser and the ice man. People planning to buy ice bought books of tickets in advance. These coupon books cost six dollars and contained six dollars worth of tickets in four different colors, each color representing one of the sizes of hunks of ice available. Mother kept her ticket book in the drawer of the kitchen cabinet and then placed the right color for the amount of ice she needed on the shelf between the two back doors to the ice box.